29th April 2025

The Great Mughals: Art & Opulence at the V&A

Recently I visited ‘The Great Mughals: Art, Architecture & Opulence’ at The V&A, which showcased a stunning collection of Mughal art, ornate objects and artefacts from the Golden Age of the Mughal Court (roughly 1560–1660), spanning the reigns of its most renowned emperors: Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan.

Having written my dissertation on the iconic Mughals in 2014, I have long been fascinated by their patronage of the arts. My dissertation focused on the traditional turban ornament, known as the ‘sarpech’ and its symbolic connection to power and grandeur within the Mughal empire.

Visiting this exhibition was a dream come true for me, as I had the opportunity to see many of the paintings, objects and historical materials I referenced in my dissertation in person for the very first time.

I stood in awe, studying the intricate details and extraordinary craftsmanship in each painting and royal object, absorbing every bit of information about the works on display.

Among the many remarkable pieces of Mughal art, there were a few that truly stood out to me:

Ornate Daggers from Jahangir’s Period

Created in the Mughal Court Workshops, ornately decorated daggers, swords, and scabbards were highly valued ceremonial items during Mughal Durbars. These objects, which displayed the immense wealth of the empire, were primarily ornamental and not intended for use in battle.

The examples in the Victoria & Albert Museum, dating from around 1600-1620, feature precious rubies, emeralds and diamonds intricately set or inlaid into gold using the traditional kundan setting technique in India. The pieces are further adorned with delicate chased and engraved floral patterns. The core of the handles are crafted from iron, while each weapon is equipped with a beautifully patterned watered steel blade.

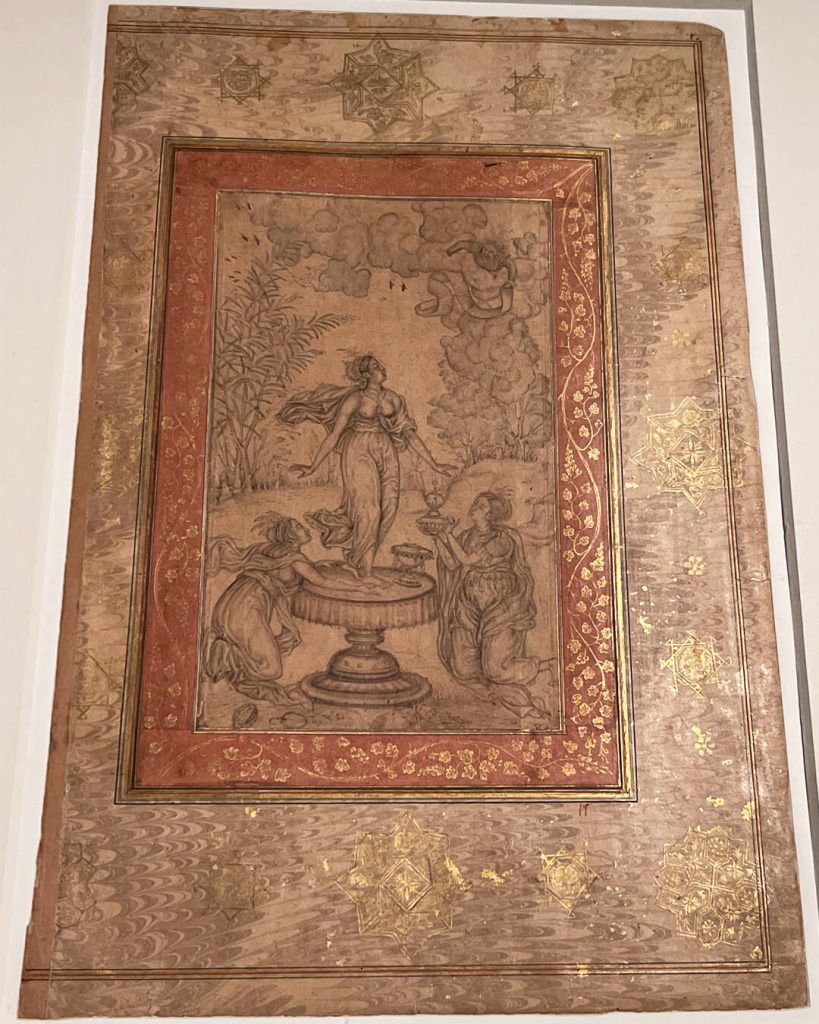

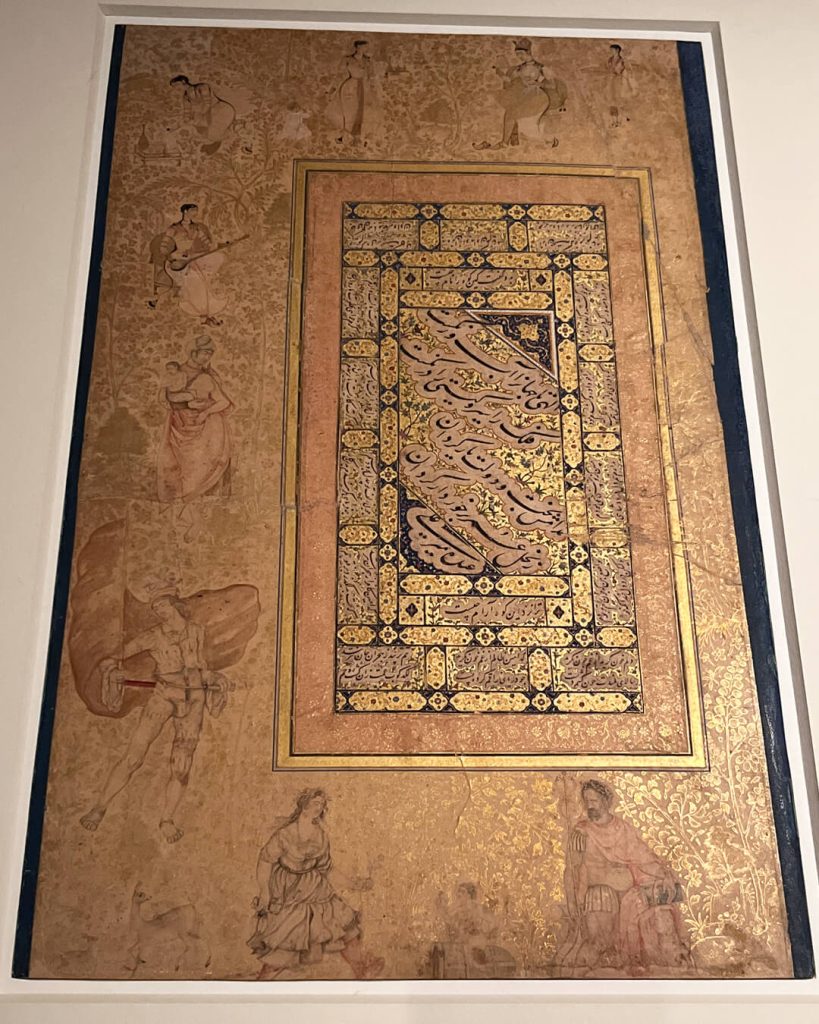

European Images in Mughal Art

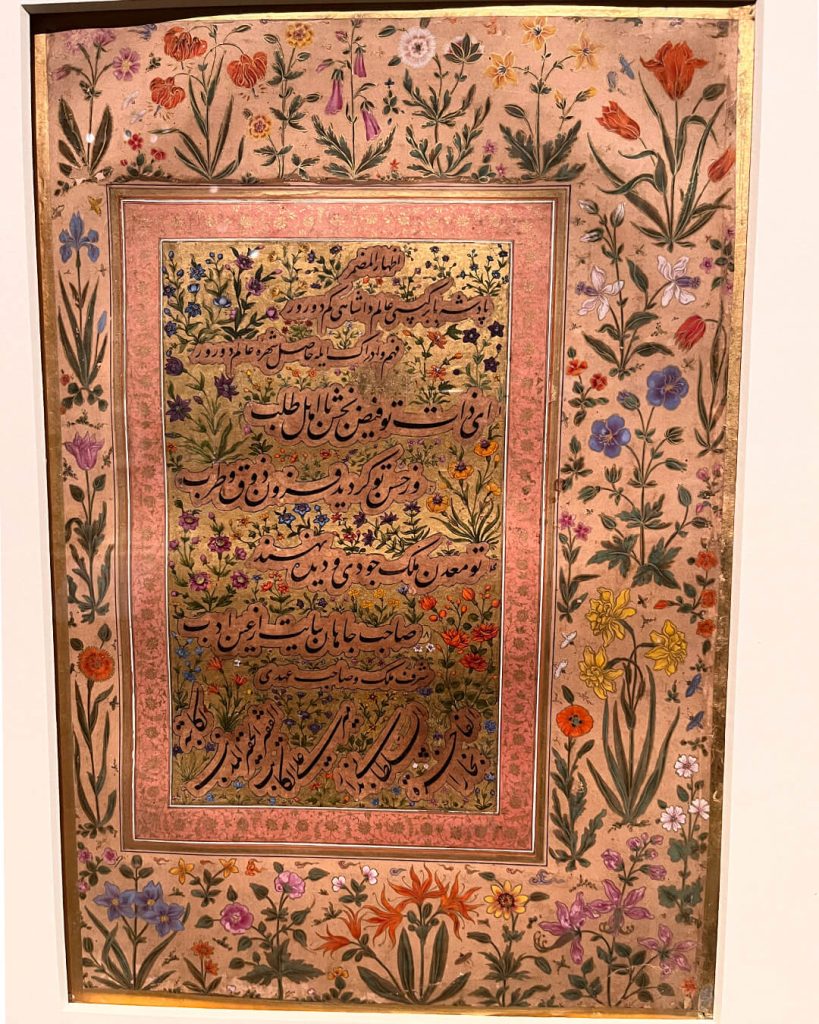

I was deeply struck by the Mughals’ appreciation for art and craftsmanship from across the globe. One of the most captivating examples I encountered were paintings in the Gulshan album, dating back to Akbar’s reign (1500-44). These works feature European engravings given to Akbar by the Jesuits who visited his court. The engravings, which depict allegorical European figures, were carefully recreated by Mughal court artists, who framed them with decorative Islamic patterns.

This fusion of European and Islamic styles beautifully showcases the Mughals’ respect for different artistic traditions and their ability to blend cultures in a harmonious way.

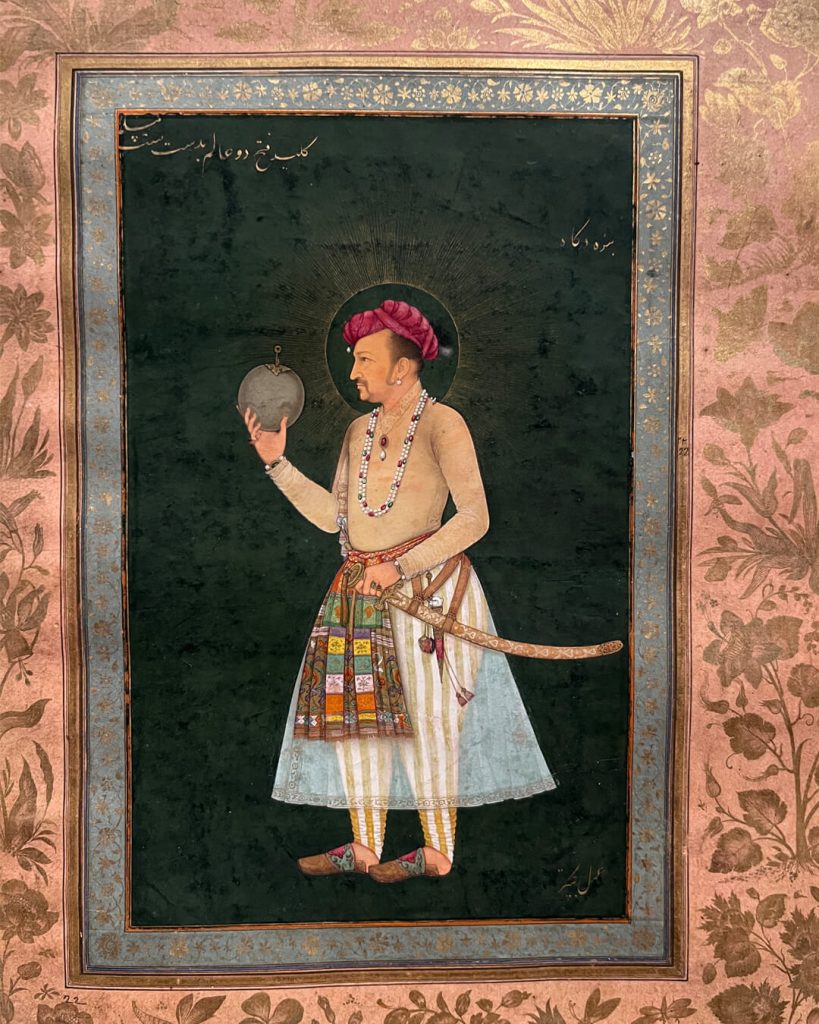

Jahangir’s Gold Zodiac Mohurs

Having inherited a vast and prosperous empire, Jahangir’s reign saw the arts thrive, with his court famously known as ‘the treasury of the world.’ His passion for the arts was evident, and in 1618, he commissioned a set of 12 gold coins, or ‘mohurs,’ each featuring the signs of the zodiac.

As a jeweller myself, I was struck by the intricate craftsmanship of these coins, with detailed carvings of the zodiac on one side and flowing Persian script on the other. They were truly a sight to behold!

Shah Jahan and Ulugh Beg’s Spinel

Spinel is one of my favourite gemstones, admired for its high lustre, brilliance, and stunning range of colours. I often incorporate spinels into my jewellery designs, so I was thrilled to see an exquisite example of this gem at the V&A. Often overlooked and historically mistaken for rubies, spinel has a fascinating history – perhaps most famously in the case of the Timur Ruby in the British Royal Collection, which was reclassified as a spinel in 1851!

The remarkable example in the exhibition is a massive 249.3-carat natural red spinel from the al-Sabah Collection. This gemstone features inscriptions from various rulers, including Mughal emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Sent to Jahangir by Shah Abbas of Iran in 1621, it was passed down through generations of rulers. In 1635, this stunning spinel was prominently featured in a new golden throne created for Shah Jahan.

I’ve long been inspired to use spinels in my work, particularly because this beautiful gemstone, with its shades of red, pink, grey and lilac, was so highly prized in the Mughal court.

Intricately Carved Mughal Emeralds

The Mughals were known for their admiration of large gemstones, and many impressive examples from their collection still survive today. Among them are these strikingly large emeralds, hand-engraved with floral and abstract motifs – a characteristic of gemstone designs from Shah Jahan’s era.

These emeralds, of Colombian origin, were brought to the gem markets in Goa by the Portuguese in the 1600s. Like rubies and spinels, emeralds were often strung on pearl necklaces and worn by emperors, their sons, wives and daughters as symbols of royalty.

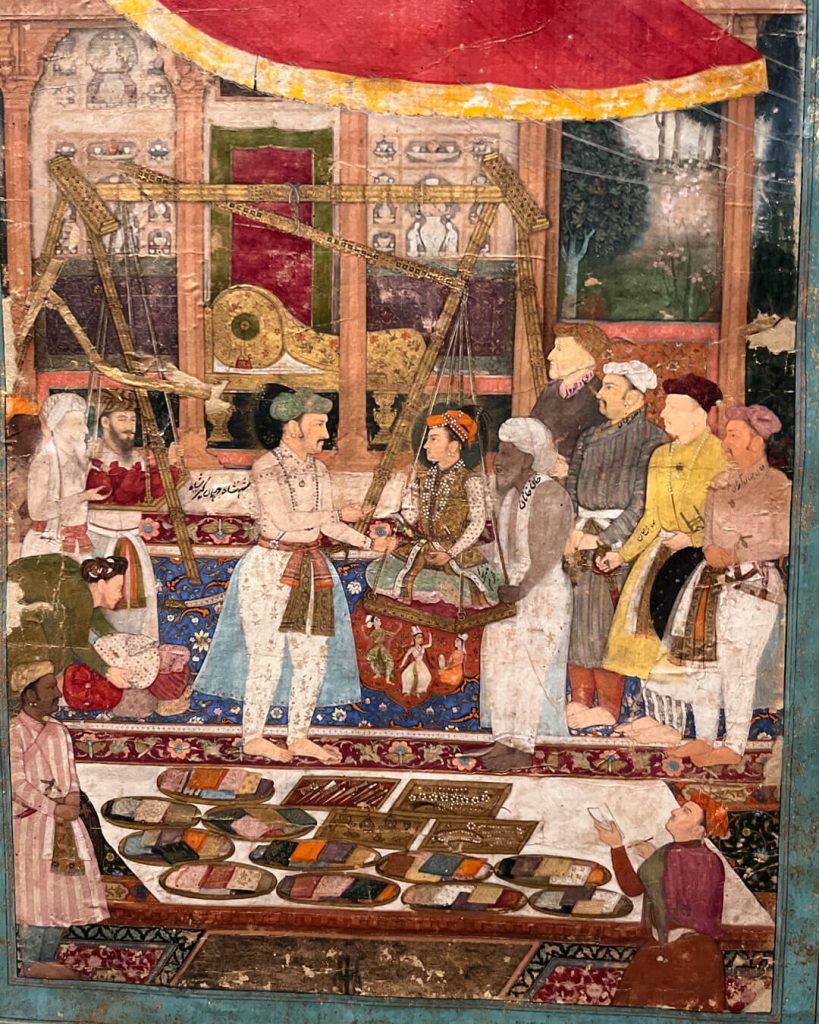

Jahangir Weighing His Son, Prince Khuram, the Future Shah Jahan Against Precious Objects, in 1607

This famous painting, which I referenced in my dissertation, ‘Objects of Imperial Power and Status During the Mughal Empire’, back in 2014, depicts the grand spectacle of Prince Khurram – later known as Shah Jahan – being weighed against a variety of precious objects on his birthday in 1614.

In the foreground, you can see bejewelled daggers, pearl necklaces, and golden vessels used as weighing objects, highlighting the lavishness of the ceremony. This remarkable piece of Mughal art appears in the Jahangir Nama (‘Book of Jahangir’).

Mughal Thumb Rings

Archery was a popular sport during the Mughal era, and as with everything they did, ornate ceremonial versions of equipment were created. These thumb rings were designed to protect the archer’s hand from the bowstring as it snapped back after a shot. However, these particular rings would have been worn decoratively during a Durbar, rather than for actual use in the sport.

Both rings are set with precious rubies and emeralds in yellow gold. The ring on the left below is handcrafted from Nephrite jade and the ring on the right features intricate enamel work, or ‘meena’, on the inside.

What I love most about these enamelled rings is how it is thoughtfully considered from every angle. The part that remains unseen by anyone but the wearer is just as exquisitely decorated. This tradition has continued in Indian jewellery, where fine pieces are often enamelled on the back, in harmony with the precious gems on the front.

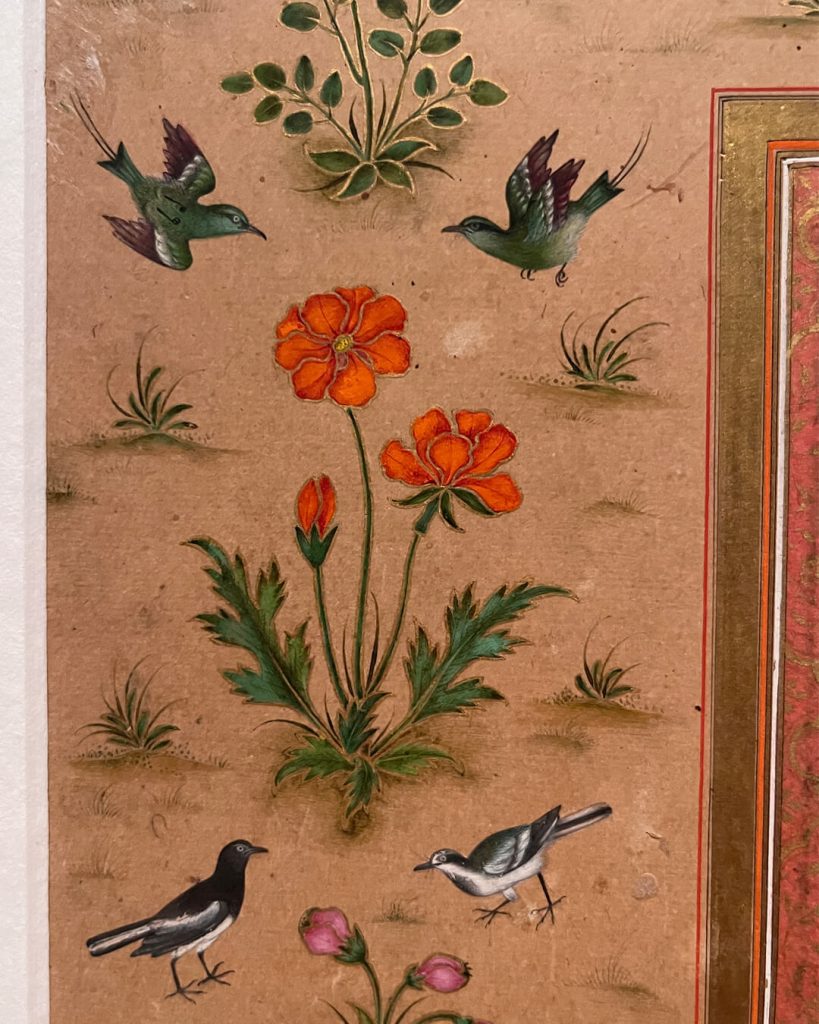

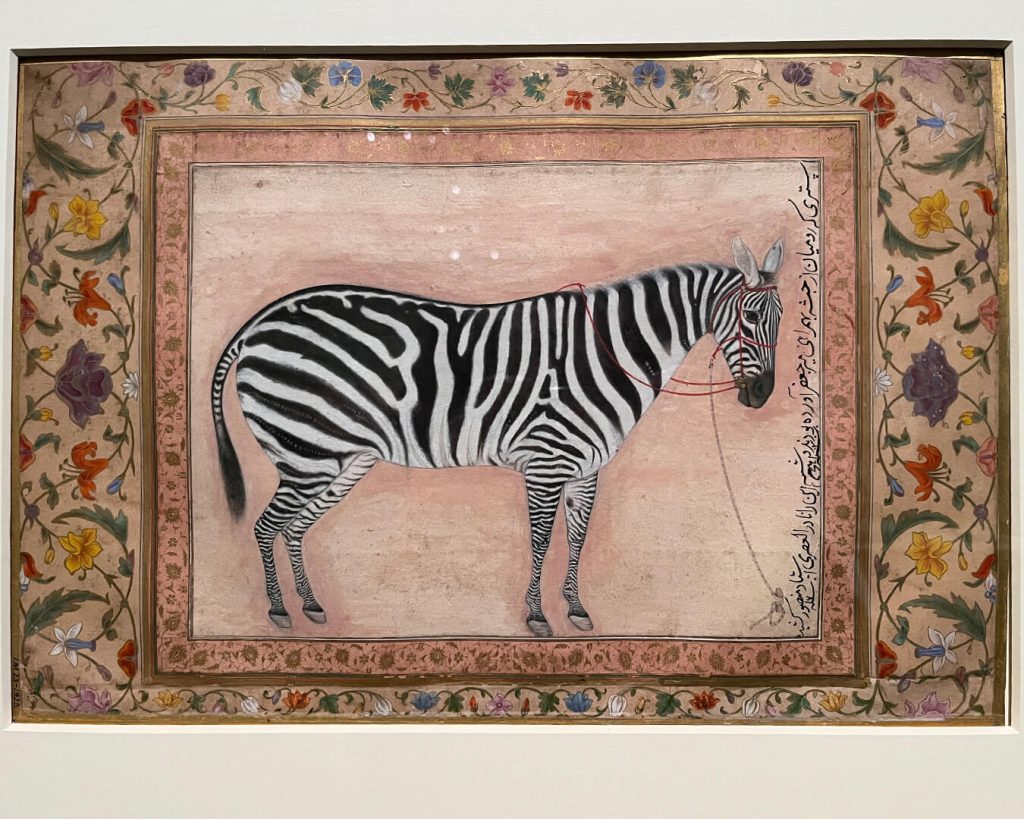

Mughal Botanical Drawings

Jahangir had a deep passion for the natural world, and during his travels, he carefully recorded his observations of the plants and animals he encountered. This passion is reflected in the work he commissioned from royal court artists. Mansur, a highly regarded painter in the Mughal court and a favourite of Jahangir, played a key role in bringing these observations to life.

Many Mughal paintings feature borders filled with botanically accurate depictions of flowers, arranged decoratively on the page. Interestingly, these floral designs were inspired by European artwork, particularly the ‘Florilegium’ paintings of Adriaen Collaert (1560–1618), a Flemish designer and engraver. Collaert’s work greatly influenced Mughal court artists, who, under Mansur’s guidance, carefully copied his designs.